Back Issues

A few back copies remain available of some issues; those no longer available in hard copy can be supplied in PDF. Please inquire about copies of issues still available as hard-copy or obtaining PDFs.

Subscription Info

Upcoming Issue

The Bruckner Journal is published three times a year, in March, July and November - since 1997 - and is available by subscription only.

Volume Twenty-Eight, Number One will be published in March 2024. Should you wish to contribute an article, short essay, letter or comment to the Journal, on any Bruckner-related subject, please contact us.

Page 3...

The first movement of the Sixth and the new Finale for the Fourth are akin in style in certain ways and even share some musical ideas—and both of them reflect his new interest in comprehensibility. It is telling that these movements contain only traces of the dense stretto-like passages of imitation that Bruckner had created few years previously, somewhat awkwardly in the earlier version of the Fourth and very effectively in the Fifth. Instead they use contrapuntal methods in a new, different way; in effect, Bruckner now has isolated and extracted elements from the classic devices of counterpoint to apply them in ways suited to the demands of effective, comprehensible symphonic composition.

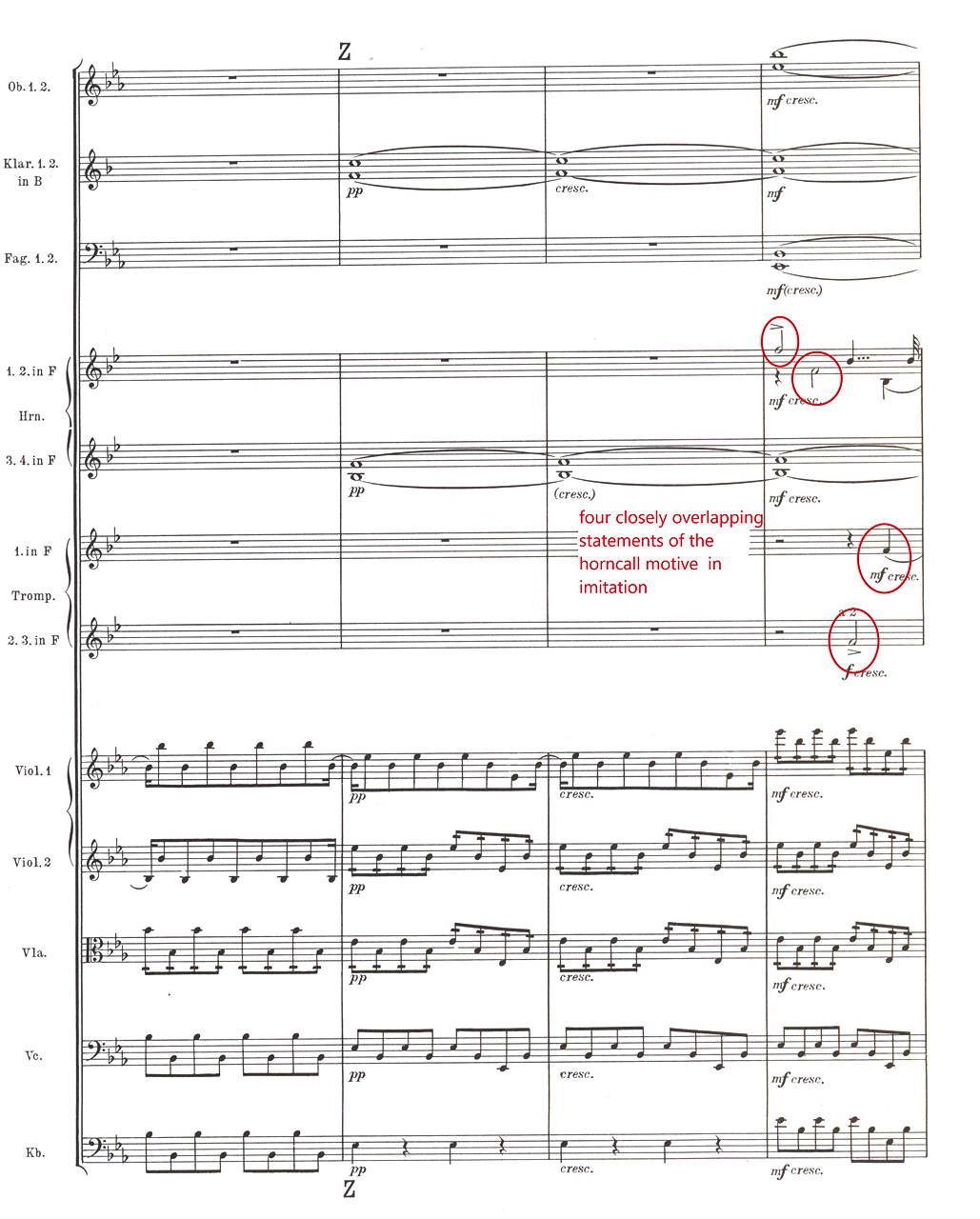

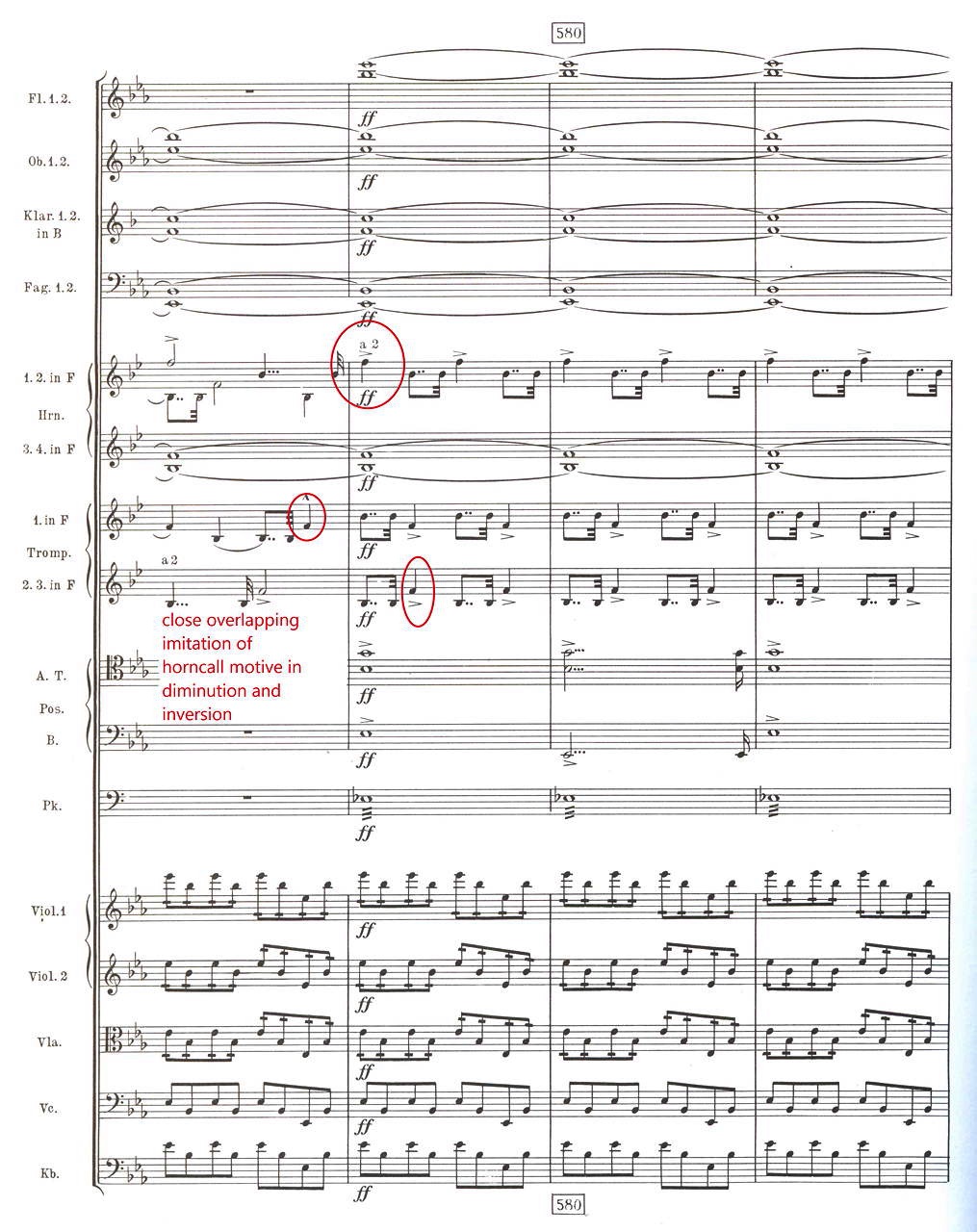

A comparison of the coda of the first version of the Finale of the Fourth Symphony and the new version completed in 1880 will illustrate Bruckner’s new manner. Although some of the leading thematic material remains the same, the character of the music is absolutely different. In the first version, the final wave of the coda begins with overlapping imitation of the symphony’s opening horn-call in shorter note values. Soon the opening horn-call returns in its original form, while the main theme of the finale appears in close imitation.

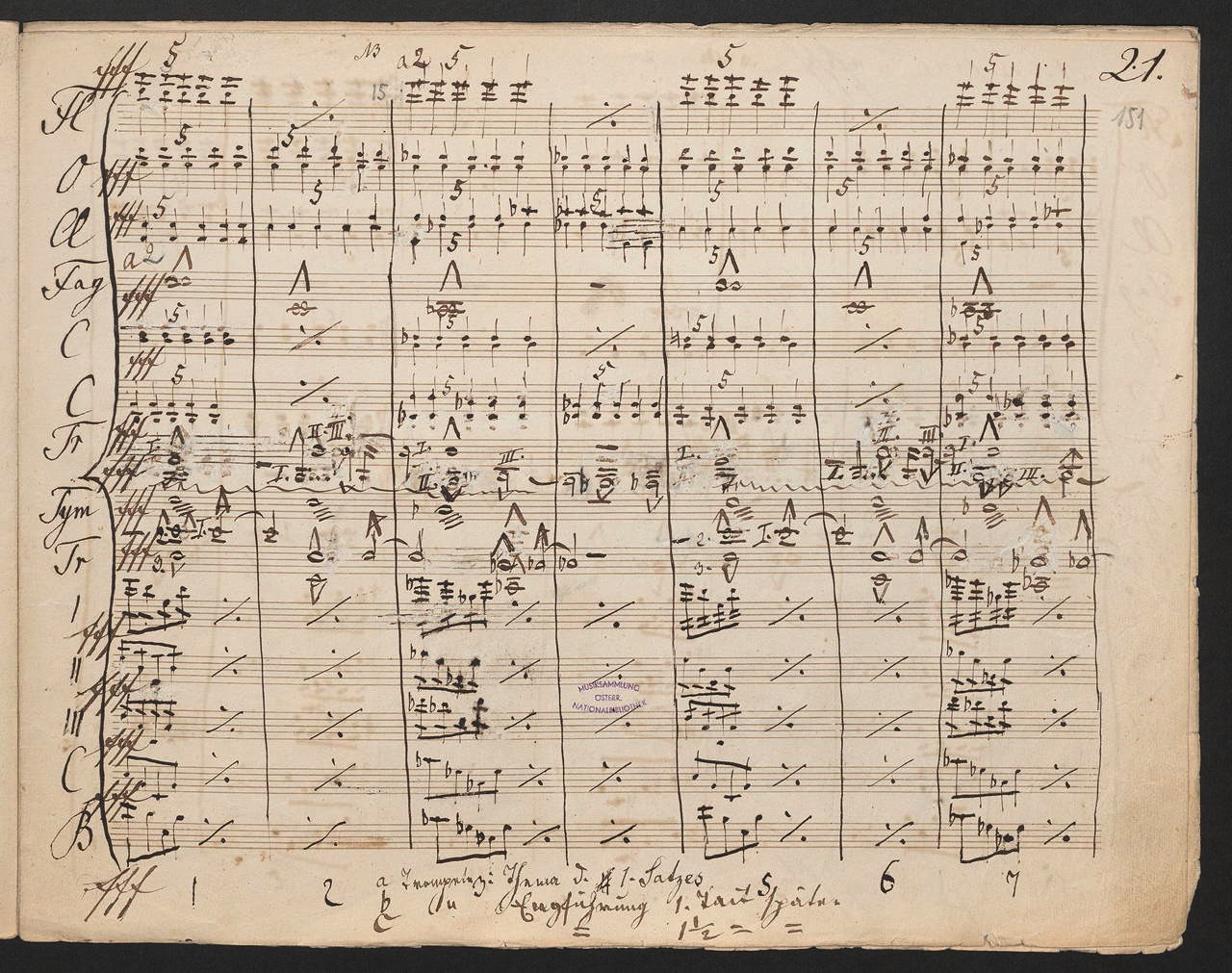

In his manuscript score, which clearly shows Bruckner’s additions, he even added a comment to explain the organization of some of the imitative, identifying the organization of the stretto (or in German, Engführung):

This level of contrapuntal intensity continues to rise almost until the very end of the symphony, when the trumpets at last ring out their final call:

This passage presents a sort of controlled chaos, with its thickets of imitation in the brass sections, which saturate the air with their chiming echoes, producing a wonderfully dense soundscape—and certainly magnificent in its own way. It is not, however, comprehensible so much as dazzling.

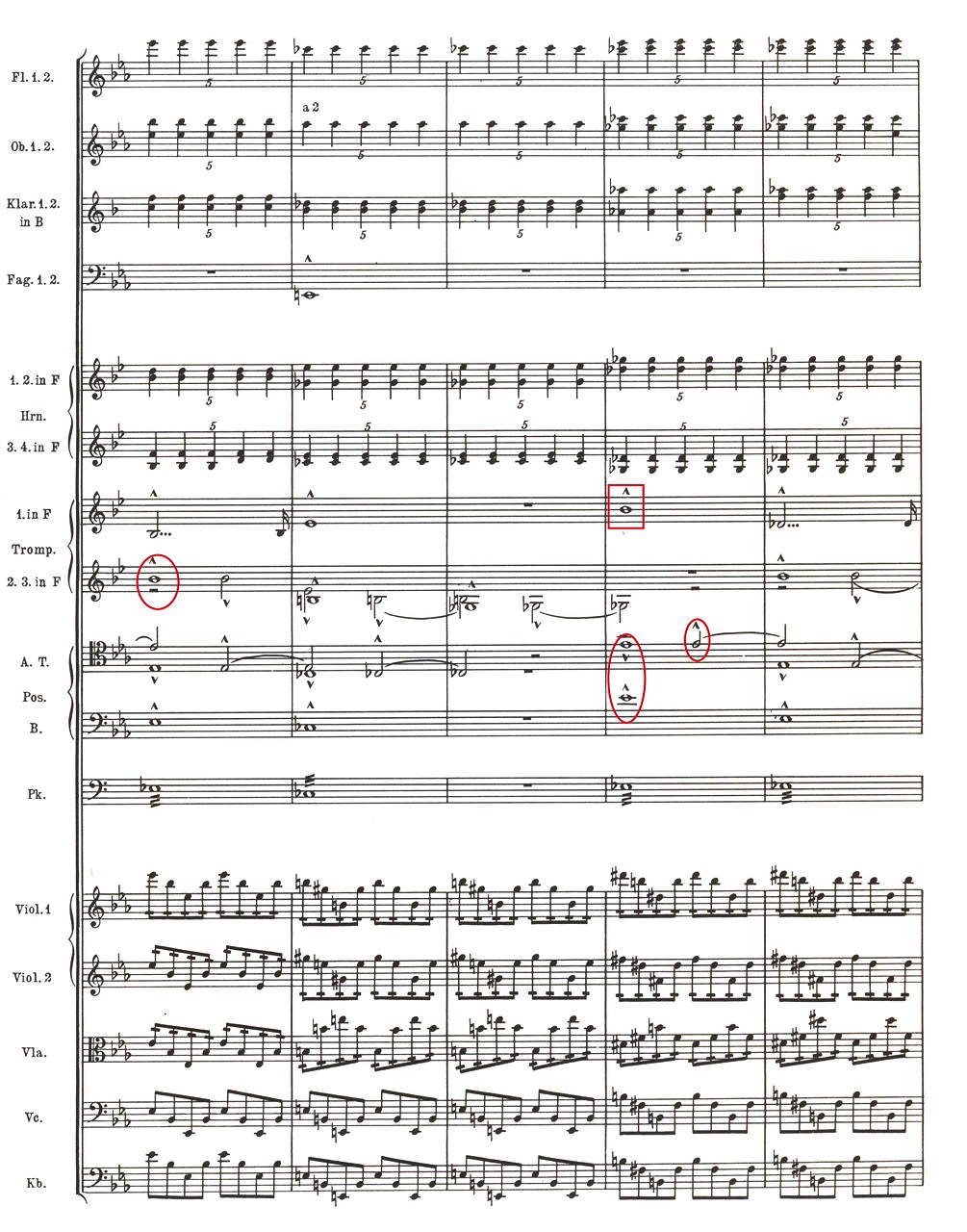

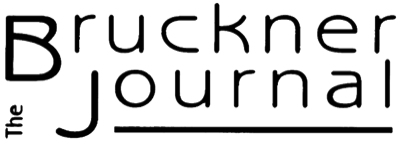

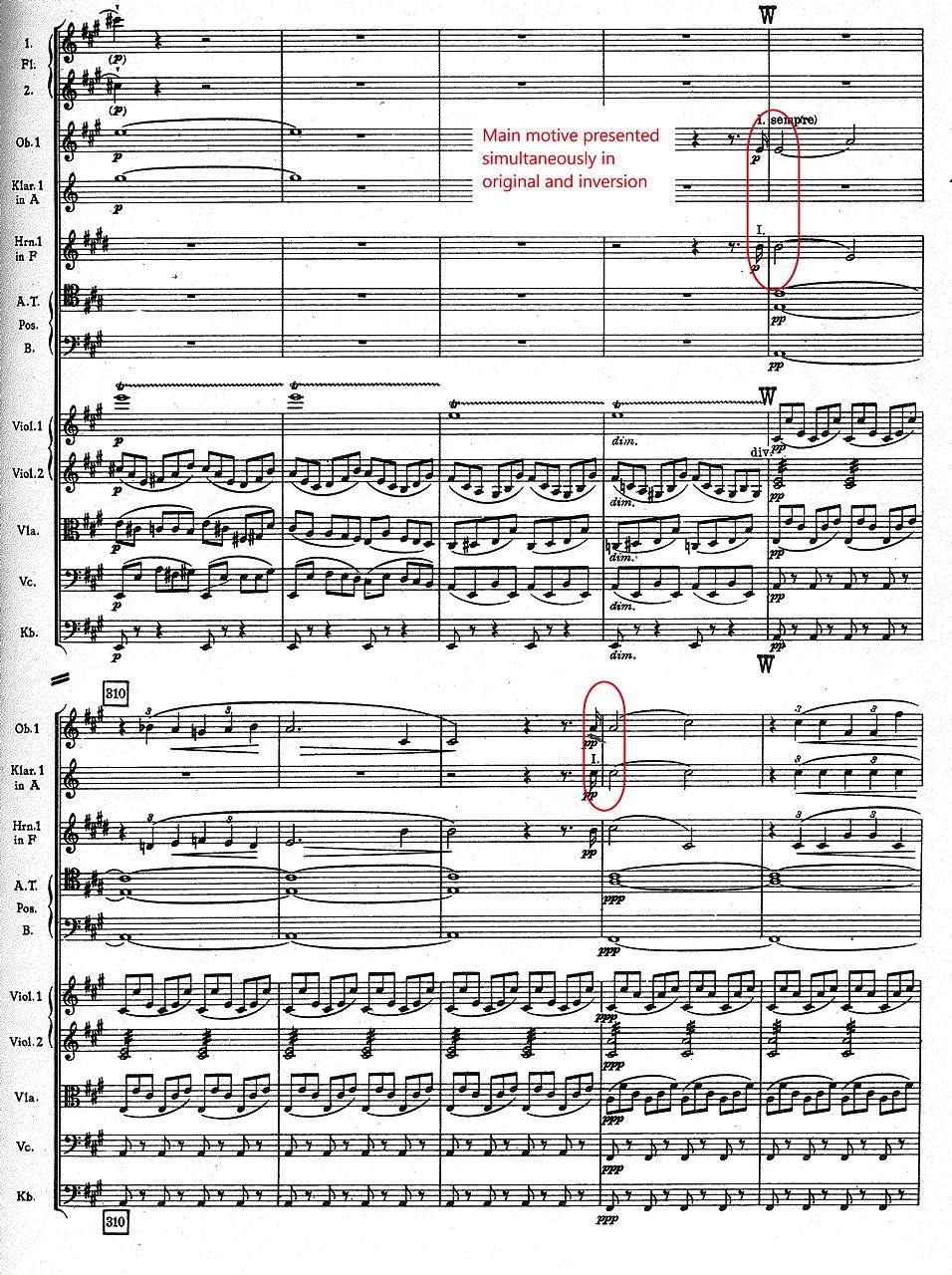

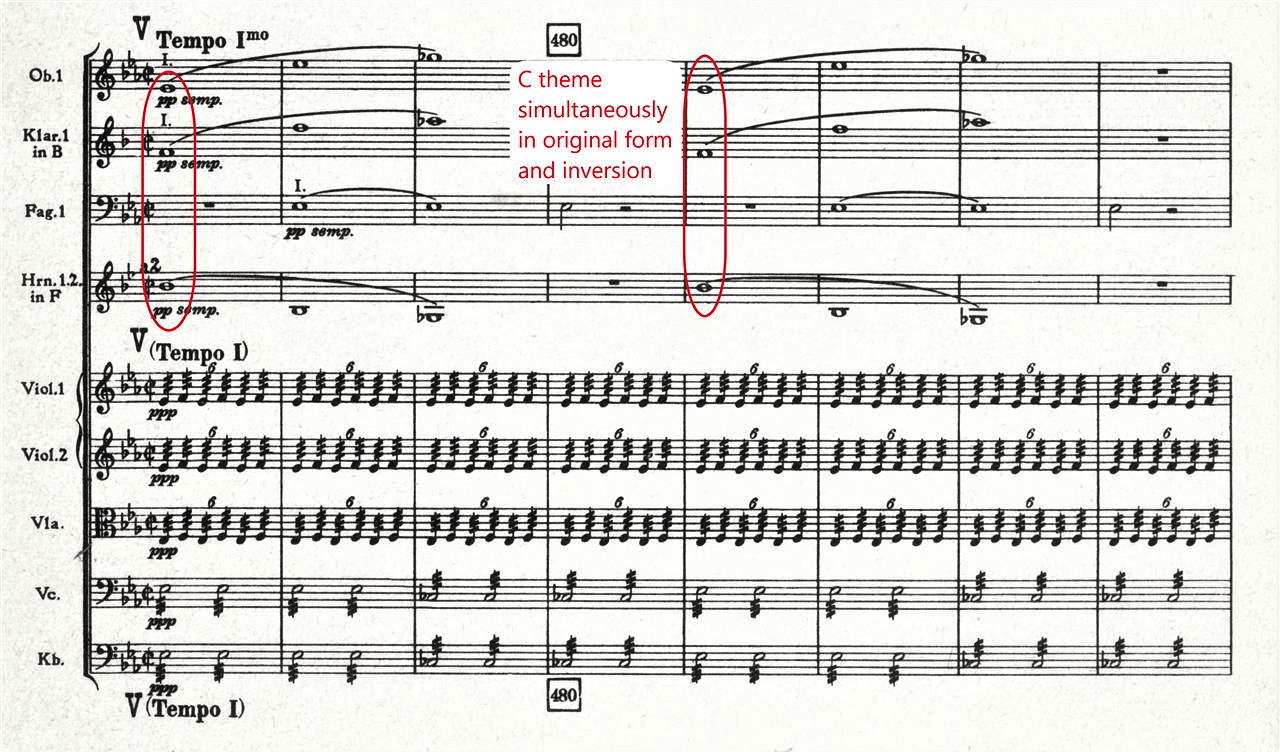

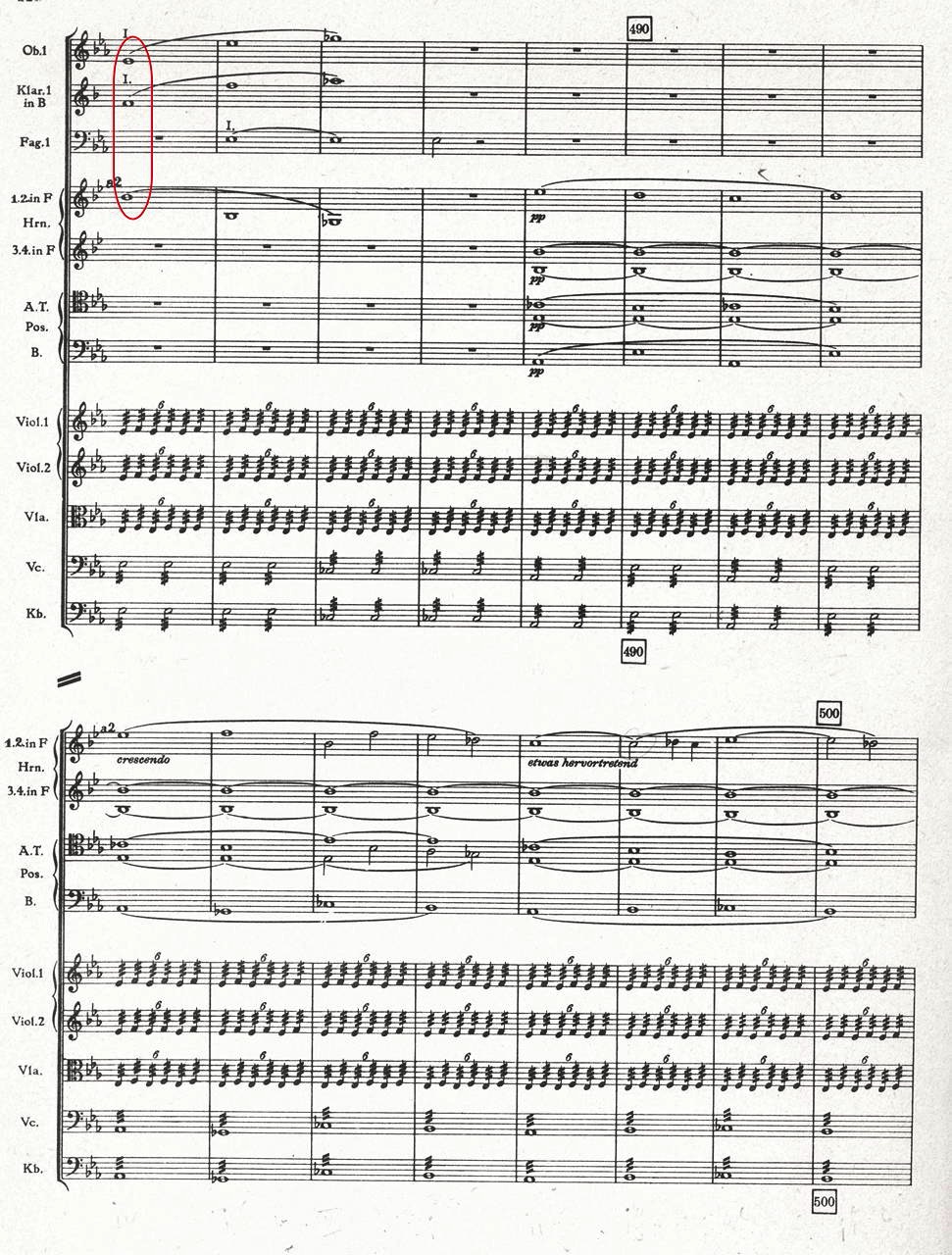

In the new version, which Bruckner composed in 1879, we hear nothing like this—no canon, no stretto, no diminution—but rather clear and structurally essential use of simultaneous inversion: with the original and the inversion appearing simultaneously.

(In striking contrast to the layer of imitation in the first version, which remains on the surface of the music, here the imitation forms the basic harmonic structure of the music and it appears several times as a basic organizing element in the music.) This music is quite austere in its texture—perhaps as a reaction against the exuberant excess of the early version—and this creates a uniquely calm intensity.

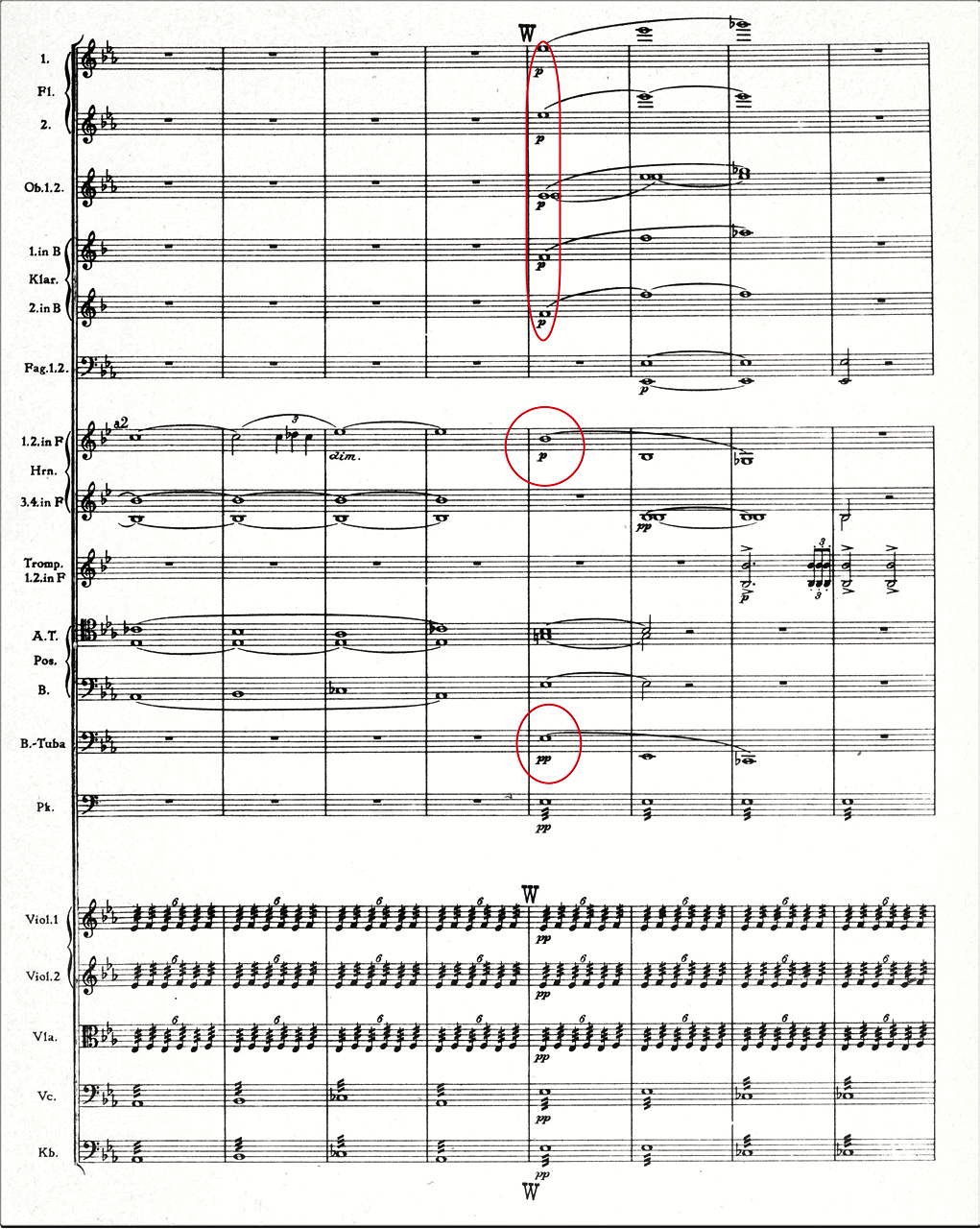

While this music is distinctly unlike the early version, it is similar in some important ways to the coda of the first movement of the Sixth. The mood of these two codas certainly differs—the one is rather dark and mysterious as it moves tautly to its final arrival in the home key of E-flat major, while the other is radiant in its major key, its calmly majestic strides, and its brilliant use of timpani and trumpet. Yet they both make great use of what could be called Bruckner’s “new contrapuntal manner.” In the Sixth this is not done as austerely as in the new Fourth, but it has nothing like the extravagance of the earlier version of the Fourth. Again, Bruckner emphasizes simultaneous inversion, now with clearly disposed imitation, with the statements successive not overlapping, creating almost a feeling of echo or dialogue across the registers of the brass and wind sections.

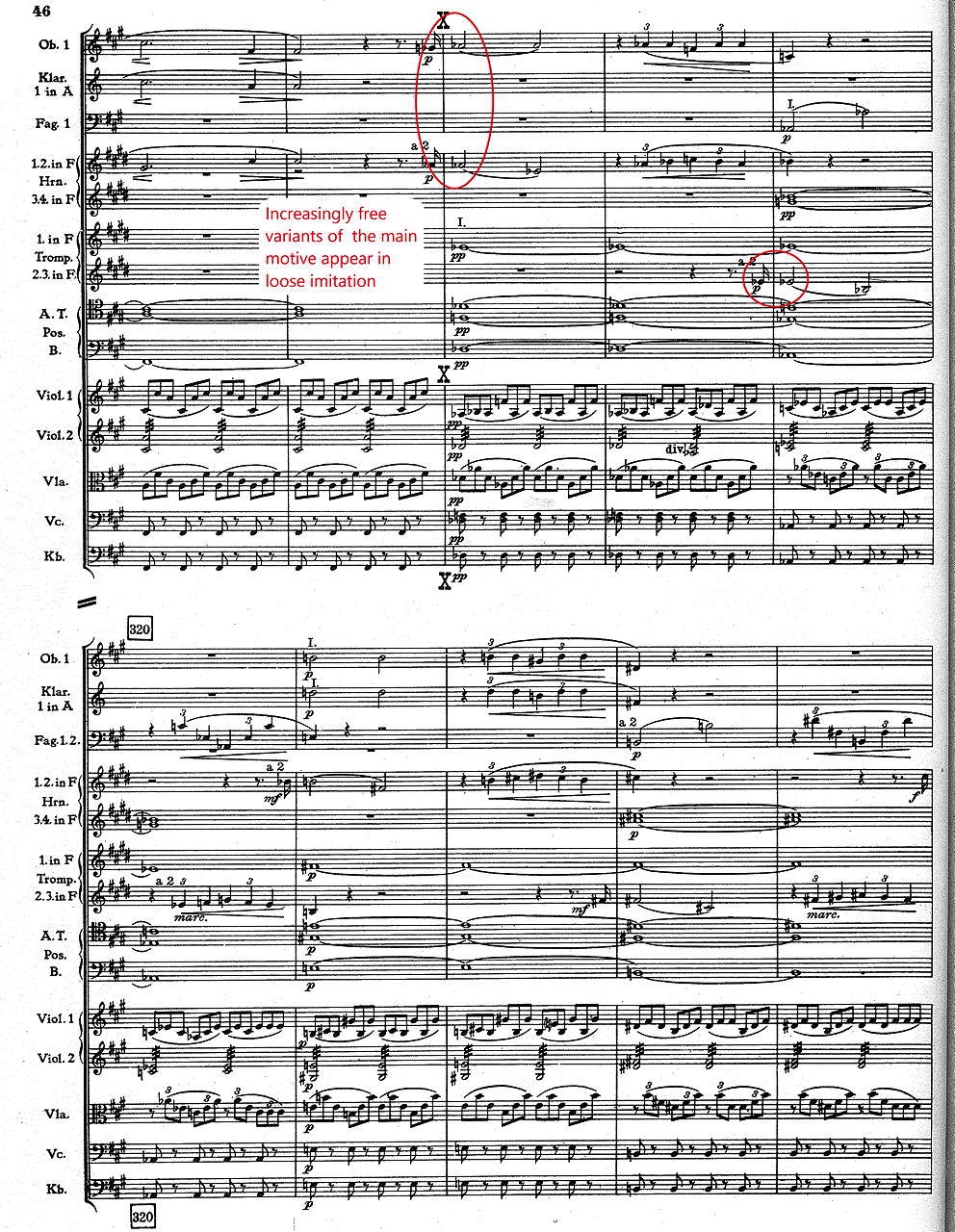

It opens with simultaneous inversion of a version of the opening theme, in horn and oboe. As horn and oboe continue this process, growing gradually less strict, a trumpet enters, echoing the horn, together with a very free inversion in the bassoon. Then something remarkable happens: the horns begins a series of entrances that are so relaxed that they feel more like a dialogue or echo pattern than actual counterpoint.

Finally to return to Tovey. In his essay on the Sixth, he commented on Bruckner’s use of counterpoint in this movement:

"The enemy blasphemes when the devout Brucknerite exclaims at the wonderful contrapuntal mastery of these devices. Technically they are remarkable only for their naïveté; the genius of them lies in the fact that they sound thoroughly romantic."

With his reference to Bruckner’s “wonderful contrapuntal mastery” Tovey here hints at exactly those aspects of his style that, as I have argued, crystallized in this symphony. Yet his suggestion of technical naiveté is surely out of place; while this music is certainly clear and comprehensible, this is not because of a lack of wisdom or experience. To the contrary, it was only by working through the intricacies he visited on the Fourth in 1875 and, far more successfully, the fugal wonders he created in the Fifth, that Bruckner was able to isolate devices derived from strict counterpoint and use them with new flexibility to enrich the musical fabric and serve the individual character of each symphony. It is not naiveté at all, then, but rather hard-won technical maturity that allowed Bruckner to achieve one of the rarest forms of creative sophistication—artful and effective simplicity. And it is this that lies behind the Homeric grandeur of this music, with its majestic sureness and the splendor of its sound.

The music examples are reproduced with the kind permission of the Musikwissenschaftlicher Verlag, Vienna

The images from Bruckner’s manuscripts are reproduced with the kind permission of the Music Collection of the Austrian National Library

The audio examples are used with the kind permission of Gerd Schaller and the Philharmonie Festiva on the Profil label

[1] Donald Francis Tovey, Essays in Music Analysis, vol. 2 (Oxford, 1936) p. 81.

[2] Bruckner: 9 Symphonies, Karajan Symphony Edition, Berliner Philharmoniker, 9 CDs (Deutsche Grammophon 477 7580).

[3] Cahis’s article is available for download at abruckner.com: here

[4] “Bruckner habe nur eine einzige Symphonie komponiert, diese jedoch neun Mal.” Quoted in Thomas Leibnitz, “Geboren unter Schmerzen: Anton Bruckner und seine Achte Symphonie,” Magazin der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien, Sept./Oct. 2011.

[5] Nowak, “’Urfassung’ und ‘Endfassung’ bei Anton Bruckner” Kongressbericht: Wien Mozartjahr 1956; rpt. in Über Anton Bruckner: Gesammelte Aufsätze (Vienna, 1985), pp. 134-7.

[6] See the “Fallow Years,” chapter 16 of Lewis Lockwood, Beethoven: The Life and Works (New York, 2003), 333-348 and “The Dark Decade,” chapter 8 of Julian Budden, Verdi, Vintage master Musicans (New Yror, 1987), pp. 104-123.

[7] Wolfgang Grandjean, Metrik und Form: Zahlen in den Symphonien von Anton Bruckner (Tutzing, 2001).

[8] “Bruckner über seine Fünfte: ‘Zu seinem Schüler Josef Vockner äußert er einmal: ‘Nicht um 1000 Gulden möchte ich das nochmals schreiben.’” Max Auer, Anton Bruckner: Sein Leben und Werk (Amalthea Verlag, 1947), p. 296.

[9] “Zu Josef Vockner sagte er damals: ‘Nie mehr schreib' i' so was, das is' mei' größte Arbeit!’ Er hatte an der Fuge Jahre lang gearbeitet.” Göllerich und Auer, Anton Bruckner: ein Lebens- und Schaffens-Bild, 4/1, p. 496.

[10] "Contrapunkt ist nicht Genialität, sondern nur Mittel zum Zweck,” letter of 22 April 1893 to Franz Bayer. Anton Bruckner Sämtliche Werke: Briefe, 1887-1896, ed. Andrea Harrandt and Otto Schneider† (Vienna, 2003), p. 218.

[11] On 12 Jan. 1875 Bruckner wrote to Moritz Mayfeld in Linz, “Die Wagner-Symfonie (D moll) habe ich noch bedeutend verbessert.“ See Röder, Anton Bruckner Sämtliche Werke: III. Symphonie D-Moll, Revisionsbericht (Vienna, 1997), pp. 22 and 119-134. William Carragan has more recently prepared a study that examines these revisions in detail, “Bruckner’s Trumpet: The Evolution of Brass Writing in Bruckner’s Third Symphony, 1873-1889,” available here

[12] Manfred Wagner, “The Concept of the First Versions of Bruckner’s Symphonies” program notes to Bruckner: Symphonies 3, 4 & 8, RSO Frankfurt, cond. Eliahu Inbal, Teldec 4.35642 (1983), p. 7.

[13] “Meine Noten von der alten unpractischen 4. Sinfonie hat mir der P.T.k. Musikdirector Herr Bilse noch nicht zurücksenden lassen.” Letter to Wilhelm Tappert on 9 Oct. 1878 in Anton Bruckner Sämtliche Werke: Briefe, 1852-1886, ed. Andrea Harrandt and Otto Schneider† (Vienna: 1998/2009), p. 185.

[14] “Gestern nahm ich die Partitur der 4. Sinfonie zur Hand u sah zu meinem Entsetzen, dß ich durch viele Imitationen dem Werke schadete, ja oft die besten Stellen der Wirkung beraubte. Diese Sucht nach Imitationen ist Krankheit beinahe.“ Letter to Wilhelm Tappert on 1 May 1877 in Briefe, 1852-1886, p. 178.

[15] “das faßlischste u. populärste meiner Werke.“ Letter to Schott Verlag, Mainz on 3 July 1886 in Briefe, 1852-1886, p. 331.

[16] Tovey, Essays in Music Analysis, p. 80.

Reference Notes

Symphony no. 6, first movement, coda, mm. 305ff

(ed. Nowak)

*click images to enlarge*

Symphony no. 4, 1880 version, Finale, coda, mm. 477ff

(ed. Nowak)

*click images to enlarge*

Austrian National Library, Music Collection

Mus.Hs. 6082, fol. 151r

*click images to enlarge*

Symphony no. 4, 1874 version, Finale, mm. 570ff

(ed. Nowak)

*click images to enlarge*